“I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work." In the winter of 1879, Thomas Edison's laboratory in Menlo Park, New Jersey, hummed with activity long past midnight. For thirteen months, Edison and his team had been pursuing the perfect filament for their incandescent light bulb, testing everything from platinum to bamboo fiber. The workshop floor was littered with discarded materials and failed attempts, yet Edison remained undaunted. Above his desk hung a placard with Sir Joshua Reynolds' famous quotation: "There is no expedient to which a man will not resort to avoid the real labor of thinking"—an ironic choice, perhaps, for a man whose career would be defined by both rigorous experimentation and creative insight.

Born in 1847 in Milan, Ohio, Edison's early life seemed an unlikely prelude to his future as America's most prolific inventor. Deemed "addled" by a schoolteacher, he spent only three months in formal education before his mother, a former teacher herself, took charge of his education. This early experience with self-directed learning, combined with a profound hearing loss at age 12—which he later claimed helped him concentrate by shutting out distractions—shaped his independent and focused approach to problem-solving.

Young Tom found his first real classroom in the railroad cars of the Grand Trunk line, where he worked as a newspaper vendor at age twelve. Between stops, he devoured technical journals and conducted chemical experiments in a makeshift laboratory he set up in a baggage car—until an unfortunate accident with phosphorus put an end to his experimental mobile laboratory days.

Edison's entrepreneurial spirit emerged early. In his teens, he not only sold newspapers but published his own, the "Grand Trunk Herald," using a small printing press he installed in a freight car. When telegraph operators along the route began sharing news bulletins with him, he discovered the value of information networks—a lesson that would later influence his approach to both technology and business. A fortuitous act of heroism—saving three-year-old Jimmie MacKenzie from an oncoming train—earned him telegraph lessons from the grateful father, launching his career in communications technology.

A folio from Edison’s Grand Trunk Herald

Edison's entry into the world of telegraphy came at a pivotal moment. The Civil War (1861-1865) had demonstrated the strategic importance of rapid communication, and the post-war years saw explosive growth in telegraph networks. Working as an itinerant telegraph operator, Edison developed an intimate understanding of the technology's limitations.

His first patent, notably, was not for an improvement to telegraphy but for an electric vote recorder—a commercial failure that taught him a crucial lesson about inventing not just what was possible, but what the market wanted.

This marked the beginning of Edison's most significant innovation—not any single invention, but the industrialization of innovation itself. His laboratory at Menlo Park, established in 1876, represented a radical departure from the traditional model of lone inventors working in isolation.

The facility was extraordinary in its comprehensiveness—Edison insisted it stock "eight thousand kinds of chemicals, every kind of screw made, every size of needle, every kind of cord or wire, hair of humans, horses, hogs, cows, rabbits, goats, minx, camels... silk in every texture, cocoons, various kinds of hoofs, shark's teeth, deer horns, tortoise shell... cork, resin, varnish and oil, ostrich feathers, a peacock's tail, jet, amber, rubber, all ores..." This exhaustive inventory reflected his belief that innovation required having every possible resource at hand.

Edison assembled a team of skilled craftsmen, chemists, and engineers, creating what he called an "invention factory." This systematic approach to innovation prefigured the modern corporate R&D lab by half a century. His talent lay not just in his own inventive capabilities but in his ability to organize and direct the creative efforts of others. Among his team were future innovators like William Kennedy Dickson, who would be crucial in developing motion pictures, and Frank J. Sprague, who became known as the "Father of Electric Traction."

The formation of the Edison Electric Light Company in 1878, with financial backing from prominent figures like J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilt family, demonstrated Edison's growing sophistication in business matters. He understood that innovation required not just technical brilliance but also financial resources and business acumen. The company's successful demonstration of electric light on New Year's Eve 1879, illuminating Menlo Park and drawing thousands of visitors, showed his mastery of both technology and publicity.

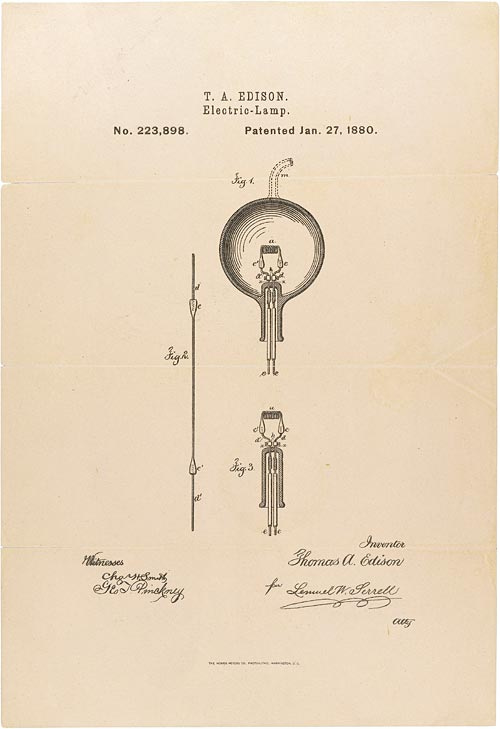

Edison’s Electric Lamp Patent from 1880

Yet Edison's very success in direct current (DC) power distribution would lead to one of the most notorious business conflicts of the Gilded Age—the "War of Currents”.

The "War of Currents" marked one of the most dramatic business rivalries in American industrial history, revealing both Edison's determination and his potential blind spots. At its heart was a fundamental disagreement about how electricity should be delivered to American homes and businesses.

Edison had built his entire electrical empire around direct current (DC), where electricity flows steadily in one direction. He had invested millions in DC power stations and distribution networks, starting with his Pearl Street Station in Manhattan that served a small but growing network of customers with power for their lights and motors.

Enter George Westinghouse, a successful industrialist who recognized the potential of alternating current (AC), a system where electrical current periodically reverses direction. Westinghouse had acquired patents for AC technology and hired the brilliant inventor Nikola Tesla, a former Edison employee who had left after a dispute over pay.

The advantages of AC were compelling: while Edison's DC system could only practically serve customers within about a mile of a power station, AC could be transmitted over much greater distances with minimal power loss. This meant that one AC power station could serve a much larger area than a DC station, making it more economical.

Edison's response to this threat revealed both his business acumen and his capacity for ruthless competition. Rather than adapt to the superior technology, he launched what today we might call a campaign of FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt). He argued that AC's higher voltage made it inherently dangerous, publicly staging demonstrations where animals were electrocuted using AC current. In perhaps his most controversial move, Edison and his supporters secretly assisted in the development of the first electric chair, deliberately using Westinghouse's AC system to associate it with death in the public mind. When the first execution was scheduled, Edison even tried to create a new verb: criminals, he suggested, would be "Westinghoused."

The battle played out in newspapers, scientific journals, and business boardrooms across America. Edison took out patents and filed lawsuits, while his publicity machine worked overtime to paint AC as a deadly menace. Westinghouse, meanwhile, demonstrated AC's superiority through successful installations and lower operating costs. The turning point came in 1893 when Westinghouse won the contract to illuminate the Chicago World's Fair, creating a dazzling display that showed millions of visitors the safety and efficiency of AC power.

The costs of this technological warfare were immense. Edison poured resources into defending DC power that might have been better spent adapting to AC technology. His stubbornness on this issue frustrated even his own supporters and financiers, including J.P. Morgan, who ultimately engineered a merger in 1892 that pushed Edison out of the electrical industry he had pioneered. The newly formed General Electric Company would soon embrace AC power, while Edison himself moved on to other ventures, although he would remain a significant shareholder in GE.

This episode teaches a crucial lesson about technological innovation: sometimes the biggest threat to a revolutionary technology isn't resistance to change, but rather the emergence of an even better solution. Edison's emotional and financial investment in DC power had created a form of tunnel vision that prevented him from recognizing or adapting to a superior technology. It was a rare misstep for an inventor and businessman who had built his career on improving upon others' innovations.

The conflict's legacy extends beyond its immediate outcome. It demonstrated how technological choices can be shaped by business interests and personal rivalries as much as by technical merit. It showed how marketing and public perception could influence the adoption of new technologies. And perhaps most importantly, it illustrated how even the most successful innovators must remain open to new ideas and willing to adapt when better solutions emerge.

Today, as businesses grapple with competing technological standards and the challenges of transitioning between old and new systems, the War of Currents offers enduring lessons about the complex interplay between innovation, business strategy, and market dynamics.

The battle ultimately cost Edison control of his electrical enterprises, which were consolidated with other firms to create General Electric in 1892. Yet this setback demonstrated another key aspect of Edison's business acumen: adaptability. Rather than dwelling on the loss of his electrical empire, he pivoted to new opportunities. His work in sound recording led to the phonograph, while his interest in motion pictures resulted in the establishment of the first film studio, the Black Maria, and the creation of the Motion Picture Patents Company in 1908—a consortium of nine major film studios that became known as the Edison Trust.

Edison's approach to invention was increasingly systematic and market-driven. "Anything that won't sell, I don't want to invent," he declared. This philosophy led him to establish the world's first industrial research laboratory at Menlo Park, where his team's methodical approach to innovation produced a stream of commercially viable inventions. His methods were so successful that by 1887, his laboratory had expanded to occupy two city blocks.

World War I revealed yet another facet of Edison's business adaptability. When the conflict cut off access to critical chemicals from Europe, Edison rapidly established his own chemical manufacturing operations. At his Silver Lake facility, he began producing phenol—essential for both phonograph records and explosives—at a rate of six tons per day. He also established plants in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, and Bessemer, Alabama, to produce benzene, previously imported from Germany. These ventures demonstrated his ability to rapidly pivot his business operations to meet market demands while maintaining his ethical principles—he notably preferred to sell phenol for peaceful purposes rather than military applications.

The war years also saw Edison take on a formal role in national defense, heading the Naval Consulting Board in 1915. However, reflecting his deeply held beliefs, he specified that he would work only on defensive weapons, later noting with pride that he "never invented weapons to kill." This period marked an evolution in his relationship with government and industry, as he began to see the importance of coordinating technical innovation with national needs.

In his later years, Edison's entrepreneurial spirit remained undiminished. His friendship with Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone led to the formation of the Edison Botanic Research Corporation, a venture aimed at finding a domestic source of natural rubber. The project reflected Edison's continuing interest in solving practical problems through systematic research—his team tested more than 17,000 plant species before identifying a promising variety of goldenrod. While the venture never achieved commercial success, it demonstrated Edison's enduring commitment to innovation and his ability to attract both technical talent and financial support for ambitious projects.

Even as he aged, Edison maintained his hands-on approach to business and innovation. In September 1930, despite his frail condition, he took the controls of the first electric multiple-unit train to depart from Lackawanna Terminal in Hoboken, personally driving it through the yard on its way to South Orange—a symbolic gesture that connected his early work in electrical systems with its lasting impact on American infrastructure.

By the time of his death in 1931, Edison had amassed an astonishing 1,093 patents and helped create multiple industries. Yet his most enduring legacy lay not in any single invention but in his systematic approach to innovation and commercialization. The organization he created at Menlo Park—combining research, development, and commercial application—became the template for industrial research laboratories worldwide. His integration of technical research, market analysis, and business strategy created a model for industrial innovation that would influence companies for generations.

In Edison's methodical yet creative approach to innovation, we see the blueprint for modern research and development. His understanding of the need to combine technical excellence with market awareness, his sophisticated use of patents and publicity, and his ability to build and manage teams of technical experts all foreshadowed the challenges faced by today's technology companies. As modern entrepreneurs grapple with artificial intelligence, renewable energy, and other transformative technologies, they face challenges that would have been familiar to Edison: how to move from prototype to profitable product, how to protect intellectual property while encouraging innovation, and how to balance technical perfection with market practicality.

Edison's true genius lay not just in his ability to invent, but in his creation of a system for invention—a method of transforming creative insights into commercial reality. As we face the technological challenges of our own era, Edison's example reminds us that successful innovation requires not just technical brilliance but also business acumen, systematic methods, and the ability to learn from and adapt to changing circumstances. In his legacy, we see not just the history of American innovation but its future as well.